The “Obsolete” Battery That Conquered the World: BYD’s Chillingly Smart Secret

Blog Post 2 of 5

In our last post, we explored the curious case of BYD’s rise in Europe, a phenomenon that defies the simple logic of brand loyalty. We saw that they are succeeding. In this post, we’ll uncover how. The secret lies in a technology many experts had written off as “last-generation.” How did an “obsolete” battery become the most disruptive weapon in the auto industry? The answer is a lesson in turning a weakness into an unassailable strength. This isn’t just about chemistry; it’s about psychology. This is the core secret that unlocks the entire Chinese EV playbook.

To understand the genius of BYD’s move, we must first understand the battery wars. For years, the industry was locked in a battle between two primary lithium-ion chemistries: NCM (Nickel-Cobalt-Manganese) and LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate). NCM, championed by leading Korean manufacturers, was seen as the thoroughbred. Its high energy density meant batteries could be lighter and smaller for a given range, making it the go-to choice for premium, long-range EVs. Its only downsides were its reliance on expensive and controversially sourced materials like cobalt, and a higher propensity for thermal runaway—a technical term for catching fire.

LFP, on the other hand, was the workhorse. It was remarkably stable and safe, boasted a much longer lifespan (more charging cycles), and was significantly cheaper to produce as it contained no cobalt. Its fatal flaw, however, was its lower energy density. LFP batteries were heavy, bulky, and performed poorly in the cold. The accepted wisdom was clear: NCM was for desirable passenger cars, while LFP was for city buses and energy storage. For years, the industry followed this path. BYD decided the wisdom was wrong.

BYD’s first move was a masterclass in reframing the narrative. They understood that while engineers obsess over energy density, the average consumer is driven by more primal emotions, chief among them being fear. As EVs became more common, so did news stories of them catching fire. These terrifying incidents created a deep-seated anxiety. BYD saw this not as a public relations problem for the industry, but as a strategic opportunity. They shifted the entire competitive battlefield away from the “Range War” and onto a “Safety Crusade.”

Their marketing was visceral and brilliant. They didn’t publish charts with kilowatt-hours. They released videos of their “Blade Battery” being stabbed with a nail. In these now-famous nail penetration tests, NCM batteries would often erupt in a violent fireball. The BYD Blade Battery would smoke a little, but it would not ignite. The message was brutally effective and required no technical explanation. It allowed BYD to sidestep its weakness in range and fight on a battlefield where it was the undisputed champion. It made a competitor’s claim of an extra 20 kilometers of range seem utterly trivial when weighed against the possibility of a garage fire.

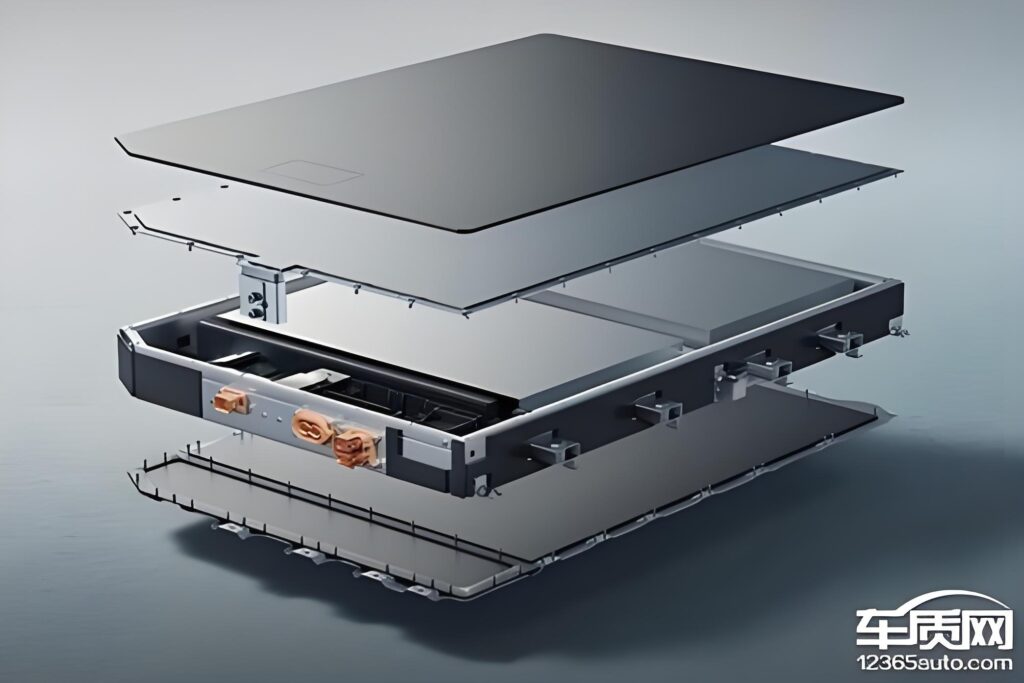

Of course, safety alone wouldn’t be enough if the range penalty was too severe. This is where BYD’s engineering genius came into play. They knew they couldn’t easily change LFP’s chemistry, so they changed its physical structure. This is the innovation of the “Blade.” Traditional battery packs assemble individual cells into protective blocks called modules, which are then assembled into the final pack. This multi-stage process, with all its extra casing and hardware, wastes a significant amount of space and adds weight.

BYD’s engineers eliminated the module stage entirely. They designed long, thin cells that looked like blades and inserted them directly into the battery pack. This “Cell-to-Pack” (CTP) design was revolutionary. By removing the redundant internal structures, they were able to fit over 50% more cells into the same volume. Furthermore, the blades themselves acted as structural beams, increasing the pack’s overall rigidity. This single engineering breakthrough almost completely closed the energy-density gap with NCM batteries. They had solved the LFP problem.

The Blade Battery is more than a piece of hardware. It is a strategic statement. It proves that innovation isn’t always about inventing a new chemistry, but about brilliantly re-engineering what exists. By reframing the debate to safety and solving the range problem with structural genius, BYD created a product that was safer, had a competitive range, and was fundamentally cheaper to produce. This “impossible” trifecta of Safety, Range, and Price is the engine powering the entire Chinese EV offensive. Now, let’s see how other companies are using this same playbook.

My AI Jazz Project: